Even though they do not metastasize, desmoid tumors often interfere with everyday activities and can be life-threatening.1,2

Labeling desmoid tumors as benign can be misleading, as they can be challenging to manage and are associated with a potentially high and multifaceted burden of illness, including pain, disfigurement, and decreased physical function.3,*

Data from a Memorial Sloan Kettering/Desmoid Tumor Research Foundation patient-reported outcome (PRO) validation study that included patients with desmoid tumors (n=31, age range 20-68, 77% female). Patients participated in 60-minute qualitative phone interviews to provide their perspectives on disease symptoms and impact on their quality of life. The majority of patients in this study were symptomatic (84%). Tumor site and type varied across patients. The concepts discussed during interviews were used to develop a draft patient-reported outcome scale, which was further refined in cognitive interviews of additional patients with desmoid tumors (n=15).3

Understanding the burden and impact of these tumors can help support your patients.

Desmoid tumor characteristics:2,3,5,6

- Rare

- Locally aggressive

- Unpredictable clinical course

- Vital organs can be impacted

In medical literature and clinical practice, desmoid tumors may also be referred to as aggressive fibromatosis, desmoid-type fibromatosis, or deep fibromatosis7,8

Examples of desmoid tumors and potential symptoms

Back

Large desmoid tumor (15 cm x 10 cm) proximal to the spine9

Image adapted from Cohen S, et al. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6:28. Reused under Creative Commons License 2.0 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0). Image background changed to gray.

Hand

Desmoid tumor causing severe restriction in the flexion of the hand10

Image reproduced from Scaramussa FS, et al. SM J Orthop. 2016;2(3):1036. Reused under Creative Commons License 4.0 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0).

Knee

MRI scan showing desmoid tumor behind the right knee associated with electric paresthesias and reduced flexion11

Image adapted from Weschenfelder W, et al. Case Rep Surg. 2015;2015:262654. Reused under Creative Commons License 3.0 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0). False color added.

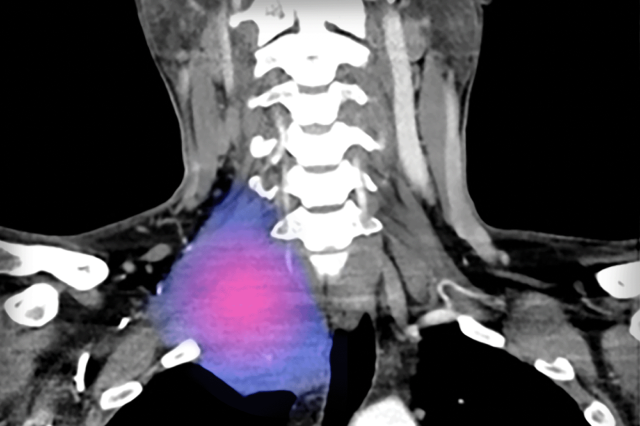

Neck

CT scan showing desmoid tumor in the right upper neck involving the brachial plexus associated with pain, numbness, and weakness in the right arm12

Image adapted from Styring E, et al. Am J Med Case Rep. 2019;7(3):36-40. Reused under Creative Commons License 4.0 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0). False color added.

Review a hypothetical case about a treatment-naive patient with a desmoid tumor.

1,000 – 1,650 annual cases in the U.S.

Most patients are diagnosed between 20-44 years of age.13-15

30%-40% are initially misdiagnosed

Desmoid tumors are commonly misdiagnosed as:16-18,†

- Hypertrophic or

procedure-related scars - Fibromas

- Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST)

- Keloid scars

- Lipomas

- Nerve sheath tumor (schwannoma)

- Nodular fasciitis

- Low-grade sarcomas

- Smooth muscle tumor (leiomyoma)

Data derived from an online survey of 130 oncologists and surgeons who treat desmoid tumors, conducted by SpringWorks Therapeutics between February and March 2022. Responses were collected from a comprehensive review of 361 desmoid tumor patient charts. Physicians (n=130) were asked to consider the primary diagnosis their patients with desmoid tumors initially received.16

ICD-10-CM Codes for Desmoid Tumors

Location-specific ICD-10-CM codes for desmoid tumors went into effect on October 1, 2023. The codes can help you document location-specific desmoid tumor diagnoses in your patients.

Identifying the earliest signs of desmoid tumor progression is key for patient management.

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) and Desmoid Tumor Working Group Guideline (DTWG) recommendations for initiating treatment:19,20,‡

Symptoms

Impairing function of daily activities

Tumor growth documented on imaging (MRI or CT)

Desmoid Tumor Progression

- Progression of desmoid tumors may be observed through both symptomatic and radiographic changes, with symptomatic progression sometimes occurring before radiographic findings21

- In focus groups and interviews, patients reported that pain was the most debilitating symptom of desmoid tumors1,§

- Evidence of pain can be a prognostic indicator of progression and can be associated with worse outcomes22

A course of ongoing observation is an appropriate option even for patients with disease progression, if the patient is minimally symptomatic and the anatomical location of the tumor is not critical. For tumors that are symptomatic, or impairing or threatening in function, patients should be offered therapy with the decision based on the location of the tumor and potential morbidity of the therapeutic option.19

Twenty-seven patients with desmoid tumors were interviewed from the Royal Marsden Hospital in the United Kingdom. Two focus groups and 13 interviews explored health-related quality of life issues and experiences of healthcare related to their desmoid tumors.1

NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®).

Systemic therapies are recommended as a first-line treatment option for progressive, morbid, or symptomatic desmoid tumors, according to the NCCN Guidelines® and Desmoid Tumor Working Group (DTWG) Guideline.19,20

Nirogacestat (OGSIVEO) is currently the only FDA-approved treatment option for progressing desmoid tumors in adult patients,

and it has an NCCN Category 1, Preferred recommendation.19

In 2024, UpToDate issued a revised review of desmoid tumor management options.23

Surgery is no longer recommended by guidelines as the first-line treatment for most clinical situations18,19

- Desmoid tumors are infiltrative and can grow into surrounding tissues, making their true boundaries difficult to identify. This can lead to compression of vital structures like muscles, nerves, and blood vessels, complicating surgical removal and increasing the risk of postoperative complications2,24,25

- Clear margins are often challenging to achieve with surgery and may require extensive resection that can lead to additional pain and functional impairment24-27

Up to 77% recurrence rates after surgical resection of desmoid tumors24,28,‖

- Surgical trauma and growth factors released during wound healing may worsen desmoid tumors and promote recurrence24,25,30

- According to the NCCN Guidelines: In general, surgery is not considered a first-line treatment option for desmoid tumors, except in certain situations if agreed upon by a multidisciplinary tumor board19

Based on retrospective, observational data. Factors associated with local recurrence post surgery include tumor location, age of the patient, tumor size, margin status, and prior recurrence.31,32

Review a hypothetical case about a patient with a recurrent desmoid tumor who had prior surgery.

Consider consulting with a desmoid tumor expert

Sarcoma Centers

You can find a registry of sarcoma centers on the website for Sarcoma Alliance for Research through Collaboration (SARC), a non-profit organization.¶

SARC is independent of SpringWorks Therapeutics, Inc. SpringWorks Therapeutics is providing this resource to help patients find healthcare professionals by location who have experience treating adults with desmoid tumors. Inclusion of a healthcare setting in this registry does not represent an endorsement, referral, or recommendation from SpringWorks Therapeutics and is not intended as medical advice. The healthcare professionals or institutions included in this registry do not necessarily prescribe or endorse any SpringWorks Therapeutics products. This registry is not comprehensive and other providers with experience treating adults with desmoid tumors may be available.

Connect With Us

Sign up to connect with a representative. You can also sign up to receive information and resources directly to your inbox.